Grace When We Fall

I (Joshua) am in my seventh year in educational administration, one of the many responsibilities I have is to work with student discipline. When I began my journey as an administrator, I used very traditional techniques and punishments with my students. I quickly realized that my strategies were going to need to change to be effective and make a difference in the lives of the children I was serving.

I (Todd) just completed my fifth year in administration and have found my experiences to be very similar to Joshua. When I started as an administrator I had this belief that every child should be treated exactly the same for the same infractions. I utilized punitive punishments and quickly began to understand the importance of diving into the root of decisions our students makes and realizing each choice, from each child, might have a different course of action to remedy.

Fight, Flight, or Freeze

Six years ago, on my first day of school as a middle school administrator, I (Joshua) was standing in the cafeteria talking to some students. As I looked to my left, I saw a student raise up from his seat quickly and punch the student beside him in the face. Quickly, I ran over to the student and calmly escorted him to my office. Since I was new to the campus, I didn’t know the student and I was thankful the student complied.

When we arrived at my office, I asked him, “why did you punch the other student?” The student was extremely angry, breathing heavily, and with an enraged stare he responded, “He touched my pizza.” As we talked, I realized that this student wasn’t eating much at home and the meals at school meant a great deal to him. It was evident that if you touched his pizza, in his mind, you were endangering his livelihood. His brain went into “fight, flight or freeze” instinct and he did everything he could to protect his food.

How was I going to change the student’s future behavior and teach the appropriate social skills moving forward? It was apparent, I was going to need to change my way of thinking and learn new skills to address the challenges of our students.

Placing students in In-School Suspension (ISS) or assigning Out-of-School Suspension (OSS) did not solve the future behaviors, due to the students still having to deal daily with hunger, broken homes, gangs, drugs, abuse, or homelessness. After spending one year on the campus and seeing the difficulties the students were facing, I turned my attention to trauma-informed strategies, restorative practices, and social-emotional learning.

I (Todd) remember a similar experience my third year as an elementary administrator. We had a child who was having outbursts almost daily and fighting with the most unlikely students. One day her behavior escalated so quickly she ended up fighting someone she had often called a close friend.

After bringing her into my office, and taking quite a bit of time for her to calm down where she could talk, we quickly identified where her anger was coming from. Four days before, on her way to school, her car had been pulled over and her father had been arrested and taken from them. The pain and fear she was carrying around was unbearable and the fact that she didn’t know how to tell anyone what happened, and frankly was a little embarrassed to tell others, overwhelmed her.

I clearly remember her telling me, “I just have so much hurt inside and am so scared about what will happen to him and us that when it becomes too much I have to let it out somehow.”

When we are able to identify the root of the trauma in that moment, we can seek to find the help necessary to help our students move forward.

Trauma is Prevalent in All Schools

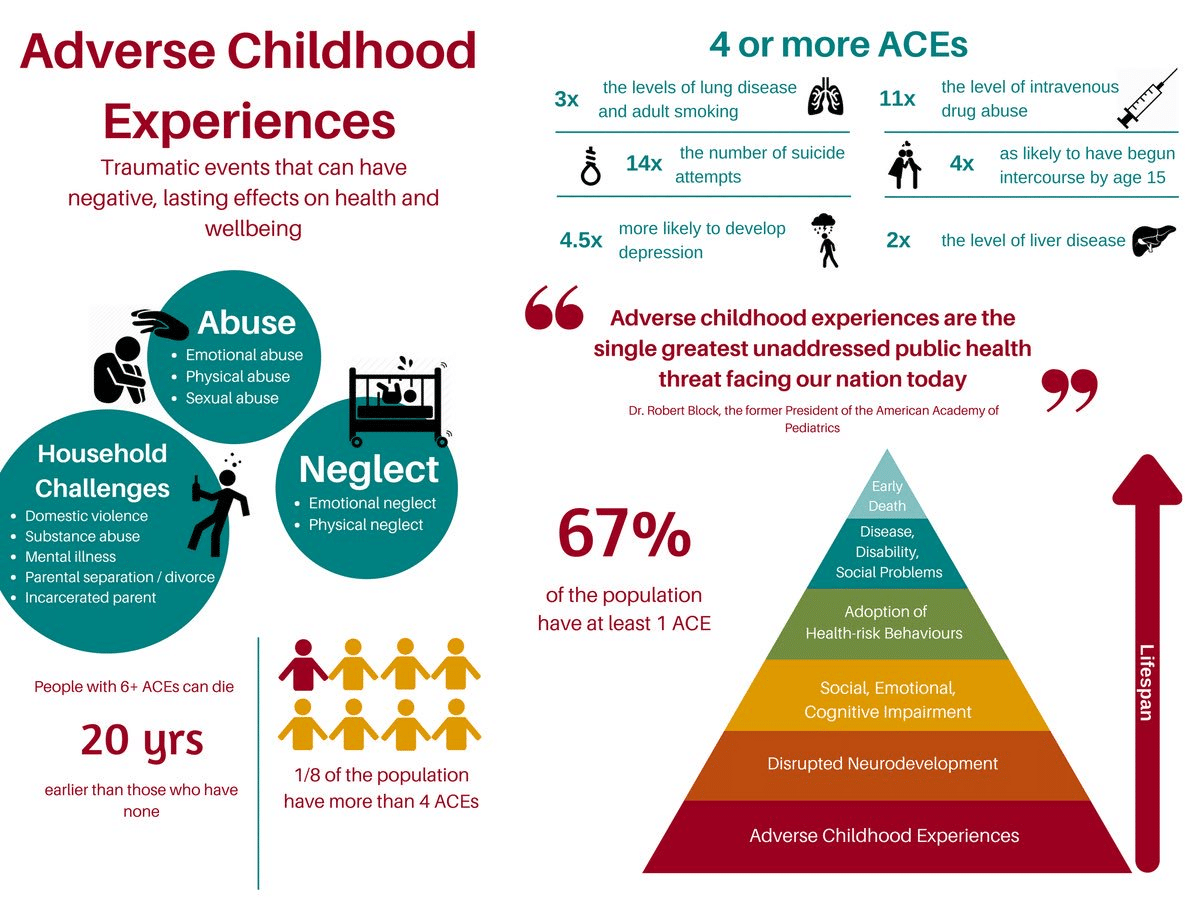

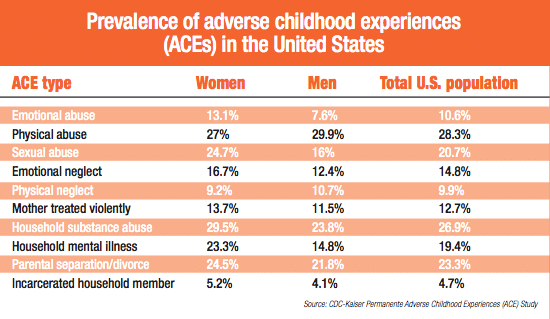

Childhood trauma is one of the greatest components our educators face today. Based on The Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE) data, 67% of our population has experienced at least one form of trauma and the statistics are only increasing. It’s imperative we continue to focus on the social-emotional needs of our students to combat the negative effects they are experiencing.

The Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE) data indicates that due to their trauma experiences, our students’ health, cognitive ability, social and emotional abilities are dramatically declining. If a student is showing signs of escalating behaviors, it is very likely that the student’s behavior is a direct reflection of a traumatic experience.

If you are interested in taking or viewing The Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE) Test, please see the link below: https://www.ncjfcj.org/sites/default/files/Finding%20Your%20ACE%20Score.pdf

Strategies Moving Forward

Mindset Change

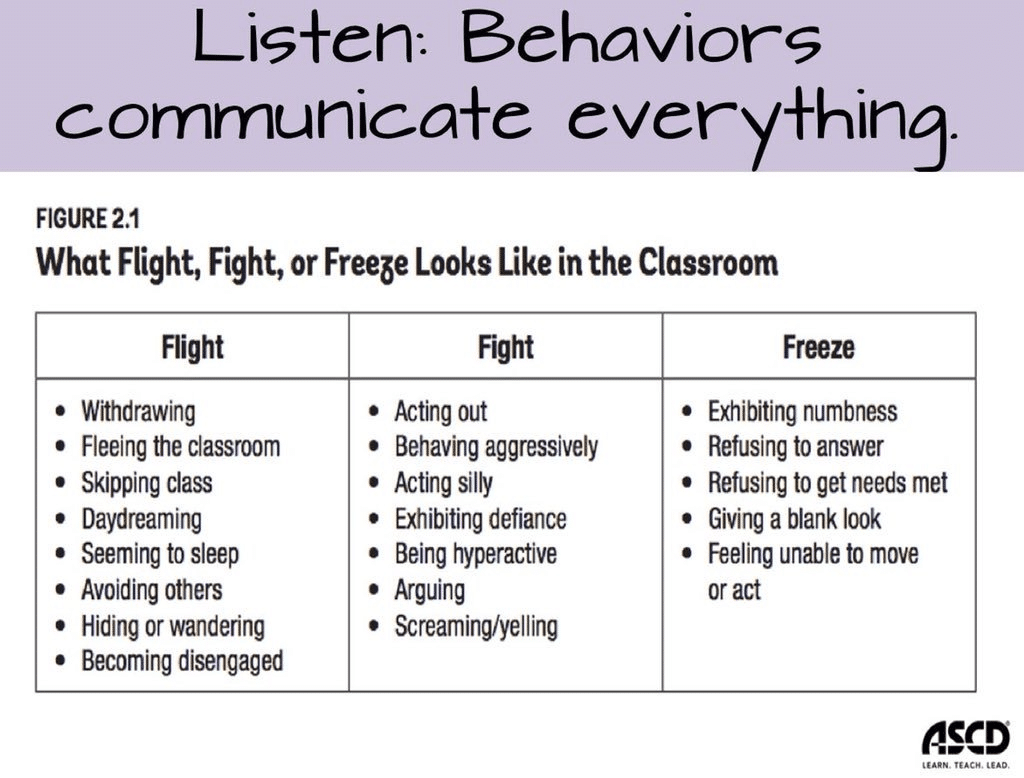

Knowing these statistics, the way we view and interact with students must change. It is often that I (Joshua) see a staff member yelling at a student to correct their behavior. The assumption is that the student will respond in a compliant and respectful manner. However, in my experience at the middle school level, often students will respond by talking back, walking away from the teacher, or shutting down completely (fight/ flight/ freeze). If our mindset is that each child has experienced trauma, our techniques and strategies are going to be vastly different. The results of negative interaction will not change unless we, as educators, change our mindsets and use our trauma-informed strategies to interact with our students.

Be a Window, not a Mirror

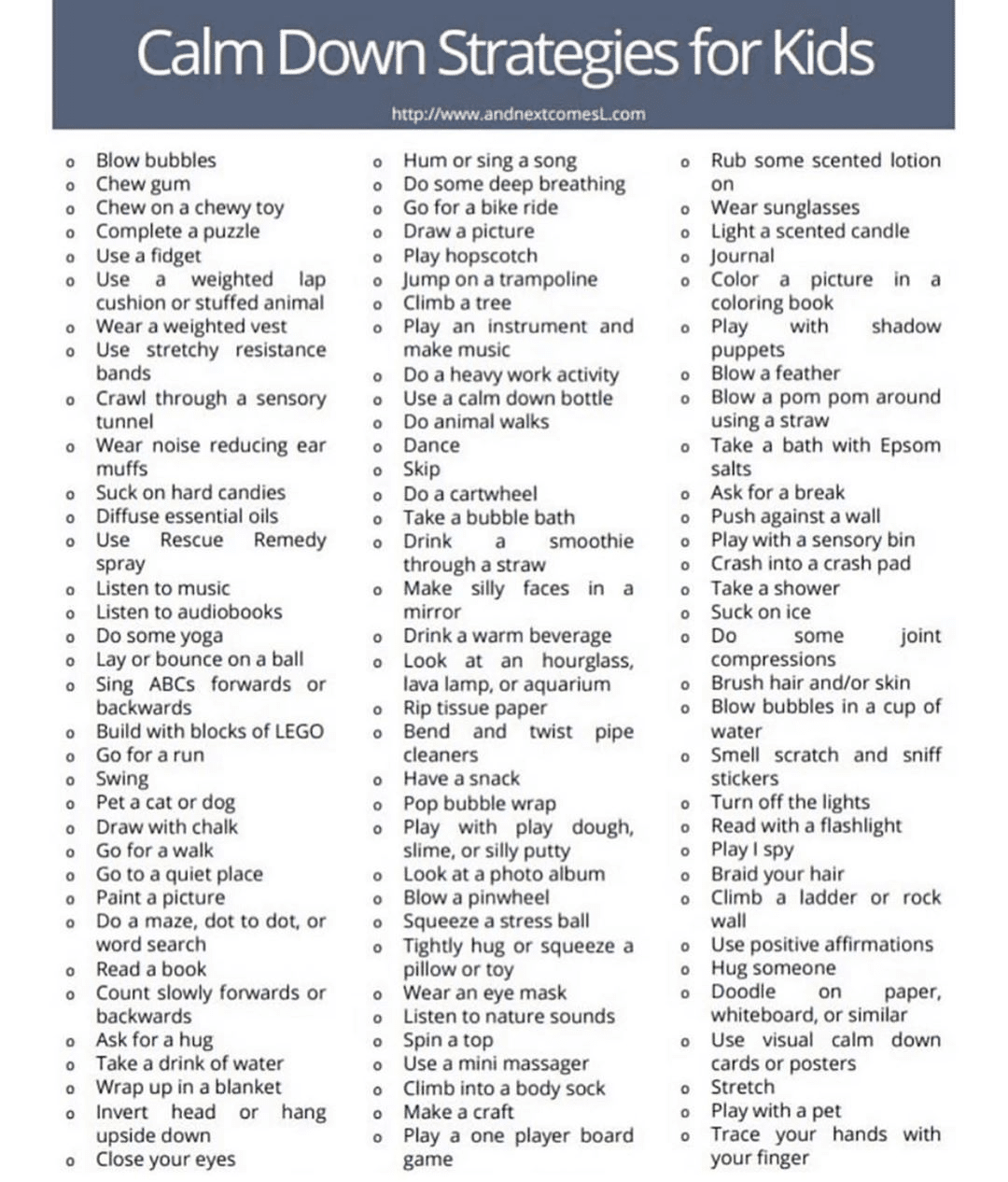

If a student escalates in the interaction, we must not match the behaviors and the high emotions of the student. To maintain a healthy relationship and model appropriate behavior, we need to remain calm and use our de-escalation strategies (see chart below).

** The list are strategies to use with students at school and/or your children at home. Not all items listed should be utilized in a school setting.

Students who have experienced trauma need an opportunity to calm down before they will be able to listen clearly, identify the problem, and rectify the damage caused by their actions.

Often times, we try to talk to the escalated student immediately with the intention of resolving the situation quickly. Both of us have found ourselves doing this countless times. It is very easy to look past the situation and focus on the tasks that need to be completed. However, if the student’s brain is in a survival state of mind, it will take an average of 30- 45 minutes for that student to regulate their emotions. We must have systems in place for students to feel safe, calm down and rectify the situation. No learning will happen, academically or behaviorally, in a fight/flight/freeze state of mind, so it’s important that we provide the appropriate time for the student to regain composure. Only once the student is calm can we begin to work with them on identifying emotions, reflecting on their choices, and determining restoration is extremely important.

Providing Grace

Another element that cannot be understated is the opportunity to provide grace. When working with children who come from unstable environments or have endured trauma, they come with even more mistrust and abandonment concerns than most.

What our children need from us are those constant reminders that their actions do not define them as a person or define the way we feel about them. Even though it’s our job to show up daily to the school, many children sit in fear of the day that we won’t return.

I’ve (Todd) made it a point as a school principal to be present at morning arrival and afternoon dismissal. I want those students who I have had to have difficult conversations with to see that I’m still there in the morning to welcome them and still there in the afternoon to wish them a great evening.

When I’m working with students through their pain, choices or anger, I always make sure that our conversation ends with the reminder that they have an opportunity to start again. An opportunity to be better, say I’m sorry, move forward, and be brave. It doesn’t mean the other people involved will be quick to forgive or move forward as well, but I remind them that the only person’s choices or emotions we can control are our own.

Providing that grace is immensely important. The grace and understanding we show to our students is an opportunity for them to see how they can in turn show grace and understanding to others. There is no one size fits all when dealing with students experiencing trauma or overwhelming emotions. It’s a case by case basis that requires supports to be in place, patience, and an overabundance of grace.